by Csilla Kleinheincz

translated from the Hungarian by Bogi Takács

This story originally appeared in Hungarian in the collection Nyulak –

Sellők – Viszonyok.

The sea droned on. A long time ago, I used to think the ocean would gurgle like river brooks, and only the magnitude of the noise would be different, gargantuan; but its size distorted all sound. It moaned like a greeting issuing from the mouths of a thousand caves. When I’d first heard it as a kid sploshing around in shorts, it had terrified me.

The audio I was getting wasn’t clear, some kind of scratching noise was mixed in with it. I twisted the knobs to get rid of the distortion.

“Can you hear it now?” The words barely made it past my headphones.

I looked up at my uncle. He was sitting in the back of the boat, his hand on the engine crank, and he bent forward closely, staring at the device glinting in the starlight. I pulled down my headphones.

“Can you hear it?” he repeated.

“What? The sea? Sure.”

“Not the sea. Them. Their song.”

“Them – you mean the whales?”

“The mermaids.”

***

I seldom saw Uncle Marlon; I spent only every second or third summer at his place, and on Christmases it was his turn to visit. He lived in a lighthouse – a true wonder for me, a boy growing up on a steady diet of pirate stories. Among all my relatives I visited in the summer – and thanks to my prolific grandparents, there were many of them – it was at Uncle Marlon’s place where I felt the strongest that I could just reach out and touch a world I had only known from books.

The tiny cottage next to the lighthouse was lit with a ship’s lantern and we slept in naval bunks. The machinery of the lighthouse with the powerful beacon and the wheels on which it rotated was constantly whirring and groaning. Barometers hung everywhere: in the bathroom, in the restroom, in the stairwell of the lighthouse, in the lookout upstairs that was always flooded with light, and also by the end of the small, rocky pier, on top of the piling.

We ate out of cans, or we munched on fish and mussels I’d pried off the sharp-edged rocks with my pocket knife. I roamed the shore in my plastic flip-flops; I waded into the small bays surrounded by boulders, not caring if I scratched my feet. By the tall wavebreakers next to the lighthouse, the water always came in strong, its foamy-white murk obscuring the sea life; the only way I could watch the crabs skittering away was by peering through the bottom of a mason jar.

I loved the lighthouse, the constant wind, the desolate seaside. My uncle I liked less. I didn’t know how to handle his rough and abrupt charity, so I spent most of my time wandering alone among the boulders. He didn’t know how to talk to me either; our days were spent in silence for the most part. But I enjoyed his stories; whenever he told me tales as the light of the beacon pulsated in the dark, tales about mermaids, ghost ships, or the drowned, I felt that I was taking part in something magical. But then the sun rose, and below the gray or – less commonly – blue skies, my uncle turned into an old man with disheveled hair and patchy, cracked skin on his knees. He wasn’t as old as he looked; he’d gone prematurely gray. Hard, snow-white stubble poked out from his face ruddy from the saltwater and the wind. Mornings, we didn’t have time to talk: he had his job to do, and I could go contemplate the seashore in quiet. We both had our lengthy silences, but their origin was different.

He’d lived by the seaside from a young age. He used to race sailboats, but once when he drove his tiny motorbike back to my grandfather’s house, he had an accident and his knee had to be put back together with titanium screws. After that, he stopped competing; he only sailed around the small bay once in a while to check up on the buoys.

He didn’t mind that the only way to town led up a lengthy series of steps. Every morning he staggered up the steps, unless I’d asked him for something or other. Then he’d send me instead. “If you need that, go buy it yourself,” he’d say.

Both the stone steps and the iron railing were slippery. I always wondered how come he never fell. But he always opted for the steps, he never took his motorboat around the cape to reach the port.

He wasn’t married. He didn’t have a dog.

I hadn’t seen him in two years. I was growing up. I started to neglect the visits to my relatives; I’d rather go on vacation with my friends, take bike trips or go rafting. Whenever I wasn’t on the road, I’d poke at the amps of our band in the makeshift studio in our garage. Surrounded by cardboard taped to the walls for sound insulation, we made noise in cacophonous abandon, our music like the bellowing of the sea.

Uncle Marlon called me in the summer and asked me to visit.

“Bring your recording equipment too,” he said. My mom had to have told him about our studio in the garage.

I didn’t know why he needed it, but the very first night we puttered out to sea in the motorboat, and only the sudden wind and rain chased us home in the end. We hadn’t gotten far: the beacon of the lighthouse winked at us through the fog of rain droplets like a giant moon.

***

“Mermaids?” I asked, rolling my eyes. He didn’t notice my expression and answered earnestly.

“Them all right. In the nighttime, they sing out there, in the sea.”

“Have you actually seen them?” I raised my voice.

He let go of the crank and lowered his fingers into the water. His yellow fisherman’s coat was glowing pale white in the dark.

“No,” he said curtly.

I didn’t respond, still fiddling with the knobs.

“I sometimes hear them, but only very distantly, when I sleep in the lighthouse. I can’t see much from the glare, and they’re too far away for the beacon to spotlight them. But they’re there.”

“Mmhm.”

“Everyone in town knows about them. Ask anyone!” He leaned away from me. “I hope they’ll be singing tonight too. At the full moon, they come closer to shore. They live out there, in the depths of the ocean, where the land isn’t visible at all; they float there and swim… There are only a handful of them. They sing, this is how they call out to each other.”

“How do you know?”

“They have to be calling out to each other. You’ll understand how.”

I finished adjusting the hydrophone and lowered it into the water. It was a highly specialized piece of equipment, I wouldn’t have bought it for myself, but my uncle’d paid up without any complaints.

Uncle Marlon was silent. I was sitting on the bare wood of the seat, staring back at the shore. The boulders arose like a black ribbon in the distance; in front of them, the bright pin of the lighthouse.

Its two eyes were blinking in turn as the bowl-shaped base of the lights rotated. The beacon didn’t reach the boulders further back: a sheet metal barrier blocked the beam, to prevent the reflections from misleading incoming ships. Three small red lights glowed steady under the blinking eyes. Above the cliffs, I could see a faint cloud of light: the town, with another smaller, unblinking beacon on its periphery.

We were still near the shore; from time to time, the beacon passed overhead, and our coats flared yellow.

In the boat between our feet stood an unlit lantern, and a basket with a thermos and two bags of chocolate chip cookies in it. I tore open a bag and started to snack on the cookies, while my uncle gazed ahead rigidly; staring at the ink-black ocean, trying to see something, anything.

I let him stare. I was cold.

I put the headphones back on. The moaning of the sea became louder compared to when I’d been listening unaided. A buzzing, sometimes a wailing like foghorns in the distance, a barely audible chirping, a groaning… it took me some time to realize that I had to have been hearing the sea life.

My mouth felt dry from the cookies, and the sweet flavor was uncomfortably satiating. I glared at my uncle. I wanted to go home and lay down on my cot.

This was when I first heard the song; it was almost sneakily quiet. At first I didn’t even realize what was happening – I simply felt a sense of longing, and only then did I notice the moaning slowly shaping itself into a melody.

I sat up in shock.

My uncle only started hearing it a minute later, his eyes widening, his bushy white eyebrows quivering. He reached out to me. He said something; I couldn’t make it out through the headphones, but I understood what he’d meant.

“Record!”

I hastened to find the correct button to press, started the recording. The tape began to roll.

The song was becoming ever louder. I didn’t hear words, only some kind of melodic wailing interspersed with the sound of the water. It wasn’t a human voice, and certainly not a woman’s voice. It was a high-pitched, burbling-sighing call, and yet it grabbed and twisted my heart. It hurt. I wanted to be out there.

I watched the sea while the beacon flashed overhead and lit the black surface of the waves for a moment here, a moment there. I couldn’t see anyone, anything. I suspected that they had to be further away, and I leaned out of the boat.

The motor roared to life and I yanked my head back. For a moment, the song ceased. Uncle Marlon’s hand slipped off the crank. His fingers were trembling. I understood what was happening inside him: he wanted to go, at any price, go out to the deep ocean, lose himself in the song, in the waves, because maybe out there, he would be able to find whoever was calling him – and yet he couldn’t do it.

We knew that the song was a trap. It hadn’t been meant for us, we had no way of responding to it, and yet, and yet…

Even though the voice didn’t sound like it belonged to a woman, I still felt that Kathy was calling out to me, that she was right there within reach, that she’d returned. I longed to touch her.

When the song ceased, I felt the cold wind bite my face where the saltwater of tears had rolled along my cheeks. The tape recorder was busy registering the moan of the waves. After long, long minutes, I reached out and turned it off, then pulled the headphones down.

“Did you manage to get it?” My uncle’s voice had changed.

“Yeah,” I responded in kind.

The motor roared again. For one last time we looked out toward the ocean, then turned back toward the lighthouse. A heavy sigh tore out of me, and we headed back, toward the blinding lights, our port of call.

***

I drove home. I threw the cassette tape onto the other seat in the old Ford I’d bought from my wages the past summer, and then I left the rocky shore behind.

A few days later, I sat down and transferred the tape onto my computer so that I could remove the unnecessary noise. I didn’t have anything better to do either way: Kathy had moved out two weeks ago. I still hadn’t realized that I could go to the movies with someone else as well. While I was working on the material, I deliberately didn’t listen to it from beginning to end – I only removed the hisses, the swishing of our windbreakers, and the sounds of human activity that had reached us from the shore. I left the melody alone; if I found myself listening in, I pressed the forward button, sweat beading on my temples.

When I was done, I copied the cleaned material onto another tape and called Uncle Marlon.

“Will you bring it here?” he asked.

I had enough time. Our drummer and our bass player had both left for Europe, and it made little sense to practice without the two of them; Kathy also didn’t fill up my spare time any longer. She used to say I spent too little time with her, but now that she’d left, I was forced to realize just how much time I had on my hands. All this had been too little for her?

So I sat in the Ford again – with the tape, my cassette deck and my old sweater, headed toward the shore. All the way there I listened to Ugly Kid Joe. The unmarked, black cassette remained untouched on the seat. I don’t even know what I’d been so worried about: maybe that once I heard the song, I wouldn’t stop the Ford by the small town built on top of the cliffs, but rather drive on, past the cliffs’ edge, and fly the gleaming car into the sea, trying to find the singer underwater.

I took the steps leading down the seawall two at a time. The iron railings were cold and slippery in my palms, smelling of metal. The sun was already setting; the lights painted bronze highlights onto the stone surface of the lighthouse and onto the sea. The reflectors weren’t running on full power yet. The wind was blowing, smashing the waves onto the black rocks, and the water sloshed back into the sea in tattered white fragments of foam.

I walked along the footpath, the duffel bag and the sweater I’d knotted onto the loops of its handles on my shoulder, the cassette tape in my pocket. The horizon had a silver sheen and the sky was overcast. The well-worn green door of the tower was in deep shadow. The house was crouching next to it, ringed by stunted, craggy bushes.

Uncle Marlon probably couldn’t hear me knock, because he didn’t come to the door. I stood on the doorstep for a while, yelled hello, then opened the door. The house was empty.

The living room looked as usual. I put down my bag, and with the tape still in my back pocket, I stepped back out of the house. The wind ruffled my hair. I crossed over to the tower and hiked up the interior staircase.

As I was headed upward, my steps echoing, my gaze fell on the variously shaped and ornamented pressure meters. They all indicated low air pressure.

Above, something was making a loud scraping sound.

I hurried upstairs, past the vantage point where the instruments of the meteorological service were hanging, and I stopped on the last stair, stunned. In the small outlook by the reflector, two huge loudspeakers stood directed at the sea, behind them an amplifier and a tape deck. Cables snaked past on the stone flooring stained by seagull guano, and then vanished into the stairwell beyond my feet. My uncle crouched by the amplifier, fiddling with the dials.

“What’s going on?” I asked him.

Uncle Marlon turned around.

“Hello!” He stepped next to me and hugged me tight. “So, have you managed to bring the tape?” he asked with a forced smile. His mustache trembled from anxiety.

“Yeah.” I put on the sweater. It was cold up there. I pointed at the amplifier. “So this is why you needed it?”

Uncle Marlon was silent for a while, then he spoke.

“I know you think this is an eccentric obsession. That’s all right. Remember when you polished snail shells all day long? I gathered snails for you. So, this is like that. This is my own eccentric obsession.”

I shrugged.

“And also,” he pointed at my chest, “you heard the song out there on the sea, too.”

“Yeeeah,” I murmured, uncomfortable. I took the tape out of my pocket and gave it to him. “Why do you want to play it so loudly? I thought it was for your own listening, every once in a while.”

He chuckled nervously. “It’s going to be good for that, too. But today, I want to call them here.”

“The mermaids?” I couldn’t hide my skepticism.

“But you heard them too!”

“I don’t know what it was that I’d heard. It could’ve been anything.” I looked out to the darkened sea, the light of the setting sun glistening on the water like a silver-filigreed veil.

“You’ll see,” said my uncle cryptically, and put the tape in the deck.

“Fine, I’ll see,” I replied. “I’ll go downstairs to make some tea. Want some?”

“I’d take a coffee instead.”

I hurried down the stairs. In the narrow, cramped kitchen scattered with crumbs, it took me a long while to find the cheap teabags. Their moldy smell turned me off the idea, and I opted for the coffee too. While the water boiled, I climbed back up to the beam enclosure.

“So where’s this interest from, anyway?” I asked Uncle Marlon.

He was standing by the railing, his gnarled fingers tight around the metal. When he looked at me, his eyes were clear and melancholy.

“Bring that chair here!”

He sat down with difficulty, stretched out his injured foot. He gestured at me to sit opposite him.

“It’s more than a simple interest, son. Not everything is out of order in here yet,” he tapped his temple. “I’m not an eccentric. I haven’t gone mad from loneliness – at least not in the way you’d assume.”

I waited.

“You’ve surely been in love.”

I thought of Kathy. The way she’d said goodbye, crying quietly, then at the last moment slammed the door shut behind herself.

“And you believed you were truly in love.”

Guilt rushed through me. My throat closed up. It’s more than just a belief, I thought.

“It’s like this with young people. They believe they’re truly in love. It lasts a month, two at most. Still, they call it love. Well, Paul, it’s not.”

He fell silent, glaring at me.

“You never met my wife. By the time you’d arrived, she wasn’t here anymore.”

I sat up in the chair. The light rotated blindingly over our heads.

“You never told me you were married.”

This wasn’t what I wanted to say. I almost blurted out, “You, with a wife?” and then I remembered how during the family meals, my mom, dad and grandma had been discussing Uncle Marlon’s lack of family ties. They all agreed that a life of loneliness didn’t suit him, and they whispered about some kind of high school love affair that’d ended badly. I was sure that if Uncle Marlon had ever gotten married, the topic would’ve come up at Sunday lunch. Mom called him on the phone frequently enough; sometimes she even took the time to visit him. She would’ve noticed a change in his circumstances. I’ve seen this happen. She has a sharp eye for these things.

“She wasn’t someone I could discuss.”

He pulled threads from the hem of his checkered shirt, at a loss. Then he looked up. “I married a mermaid.”

I made a quiet little sound, halfway between a sputter and a chuckle. I pushed it down, but Uncle Marlon still noticed. His face twitched.

“Take your time to laugh while you still can, soon you’ll see what I’ve been talking about,” he mumbled. “Until then, you might as well listen to me, right? There’s nothing to it, Uncle Marlon telling tales, right?”

“Of course,” I muttered, feeling bad about myself. There was no trace of madness in his gaze.

“Well then,” he said, looking out to sea. The wind intensified, pulling the clouds over the waves. “I don’t know where to begin. The water? The lighthouse? The time when I was still young? Or to the contrary, my old age? The way I floated through my life and believed it’d be enough to turn on the reflector and someone would find me? I had been waiting for her… But when she’d arrived, I was already old, lame and ugly.” He took a deep breath. “She got beached following the light, and couldn’t make her way back into the water. I found her. Her body was snow white, her hair green and blue like the sea. I…” His voice broke. “She stayed with me. I loved her. She was mine only. She didn’t belong to anyone else.” He closed his fingers, dropped his gaze. “She was with me for two years. Then she stole back her braid and swam away…”

He stood from the chair with difficulty.

“That was when I realized what love meant. An obsession… an emptiness… a desire to consume the one who belongs to you.”

I thought of Kathy, that kind of easy happiness hovering within arm’s reach. I knew that hadn’t been the real thing either, and yet…

“No. I don’t think so.” I stood. “I’ll go check on the coffee.”

I went downstairs. There was a burning smell from the coffeemaker – the rubber might’ve caught a little. I prepared the two cups, the spoons, slamming everything onto the counter in anger. I was upset about my uncle. Love isn’t like that, I thought to myself, no! I pursed my lips.

When I went upstairs and handed him his mug, he mumbled thanks but didn’t continue the story, and I didn’t push him either. I ambled to the railing and leaned against it, warming my fingers with the mug and watching how the waves ruffled their backs and crashed into the rocks with ever-increasing strength.

“Let’s begin,” Uncle Marlon murmured almost apologetically. I didn’t turn around.

The coffee burned my tongue, but I forgot about it as soon as the song began to play.

The amplifier added a slight resonance. The sound of pain flowed through me; I felt it trembling in my bones, then it left me behind, floated out to sea. I felt as if it’d grabbed my heart and carried it to scatter its pieces across the waves.

It wasn’t only loneliness that resounded within, but also a deep, secretive acceptance and resignation, as if the song had made anchor inside me, delineating the solid rock bed of my self. I felt a kind of wisdom flowing within it, and a triumph over melancholy. I stared at the roaring waves, confounded, unable to assimilate all this at the same time. It was as if I hadn’t heard a song but a thousand individual thoughts. My coffee cooled in the mug.

Strongest was the call. I knew I couldn’t move any closer, but still, my whole body ached from the desire to dissolve in the music; I wanted to rip off the front of the speaker and find the singer inside the machine.

Uncle Marlon leaned past the railing. His face was wet, his eyes staring at a point in the distance.

“Can you see it already?” he turned sharply toward me, his voice louder than the singing.

“See what?”

“Them! Her!”

His hungry gaze chilled me to the bone. I chugged down the oversweetened, lukewarm coffee, and shook my head. “I can’t see anyone.”

The music swelled, and it was as if it’d even disturbed the reflectors: the white light pulsed and vibrated on the waves. The sight of it made my head hurt.

Uncle Marlon muttered something. I leaned closer, assuming he was talking to me.

“Come back! Come home! I am so lonely without you…”

His whining bothered my ears. I turned away from him, but he yelled at me. “Paul!”

I whirled around. He pointed at the water.

In the distance, pale white fish jumped out from among the waves – or were they dolphins? I strained my eyes to see better, but it was dark, and the flashing beam of the lighthouse made everything decohere.

Then Uncle Marlon pushed away from the railing and rushed toward the stairs. I remained, straining my eyes to see the approaching figures. They swam fast, jumping over the frothing foam again and again, splashing back down. Four backs lifted out of the black waters, eight slim arms glistened in the light of the beacon.

The mug wobbled in my hands. They weren’t dolphins at all.

I headed down the stairs. The loudspeaker trembled with the vibrations of the song. Downstairs, I came to a halt in Uncle Marlon’s small studio, couldn’t help looking around for a moment. I was seeking traces of a woman’s touch, keepsakes, anything that would’ve hinted at a long-gone wife. I still had a bunch of Kathy’s things. She’d told me over the phone that she’d come pick them up, but I still had her toothbrush, her dog plushie and her rabbit slippers – on my bathroom shelf, my bed, my doormat.

I couldn’t see anything but well-worn men’s clothes, a fishing pole, some seashells – and the windchime which I’d made from snails’ shells polished flat. The small safe in the corner was ajar, its lock damaged long since. Uncle Marlon filled it with cheap smokes and chocolate bars. Old magazines lay on the table, and lemon slices floated in a dinged glass pitcher full of homemade lemonade.

I shook my head. I wouldn’t have minded noticing something – after I had seen the swimming figures, I would’ve welcomed the smallest sign demonstrating I hadn’t lost my mind.

I put on my windbreaker and stepped out of the lighthouse. The soggy wind slapped me in the face right away, saltwater bit my eyes. I buttoned the windbreaker and ran to the shore where the dark silhouette of my uncle stood like a new addition to the boulders.

He was standing on the very edge of the water. The waves licked at his rubber boots, drawing back only to pour over his feet once again.

“There!” my uncle pointed toward the sea. Tears rolled down his cheeks, wet his white beard. He was tense from nerves, from the waiting. “She’ll come back! And this time I won’t need her braid…” Was he laughing? “This time around, she’ll stay with me. Her song is here.”

The music unfolded above us, heartrendingly beautiful. I was sure that the entire ocean could hear it, and it would summon dazed fish, draw them in our direction. This call also yanked at my chest. If Kathy had a song, it would’ve sounded like this one: full of joy, but somehow devoid of hope.

By then I could see the figures quite well. They were women, their bodies gleaming white, their arms arcing up and down, slicing the water in clouds of water drops. They swam as if they could not see the rocks ahead, as if it would have been the same to them whether open sea or sharp rocks lay ahead. But when they glanced up and noticed us in the jagged light of the beacon, they came to a halt.

They were so close that I could make out their features. Their eyes were enormous and dark, their lips vaguely blue. On three of the faces I saw surprise, annoyance – but the mouth of the fourth one spasmed, twisted downward in a frown.

“Come here!” Uncle Marlon yelled at her. “I have been waiting! I’ll fix everything, I promise! Just come… I missed you… Why did you leave? I love you!” Emotions distorted his bristly face.

I looked back at the mermaid who arose waist-high from the water. Her breasts were small and pointy. She glanced at my uncle – I took a step back, disturbed by her gaze, even though I hadn’t been its target. It was full of sadness and reproach, bearing no trace of love.

The mermaids approached with small, jagged motions, in sharp contrast to their previous graceful swimming. At first I didn’t understand what was going on, but then I realized: the song was still calling out to them, and they had to obey it against their will.

The first mermaid covered her face and wailed, her tone mournful.

“Come here already!” Uncle Marlon yelled, impatient from desire.

I beheld his bent-over frame, the way he beckoned his wife, his arms reaching out. His fingers were trembling. Suddenly I was certain I’d had enough. I could feel the call of the song streaming from the lighthouse, the artificially amplified power; I was sure that the mermaids could sense it better than I could, and they couldn’t do anything about it. I glanced back at the first mermaid, who stared at my uncle in horror, her hands covering her mouth.

I didn’t want to see his gaze, I didn’t want it to destroy all the calm of the summers I’d spent here, to demolish the respect owed to my mother’s brother, I didn’t want to know what had happened between the two of them during those two years. Where did the mermaid live in the lighthouse and in what circumstances? Why did her unhappiness turn into such horror plain on her face?

I turned around and ran back up the stairs, tore the door open, crossed the room, and headed up to the reflectors, enclosed in the sweat-filled heat of the wet windbreaker. I developed a side stitch by the time I reached the top; I fell out into the vibrating, fluctuating light gasping for breath.

For a moment I grabbed things in a panic, half-blinded from the sweat in my eyes and from my agitation, looking for the tape recorder – but I finally found it and turned it off. The sudden silence bent my shoulders, and when it reached a deafening pitch, only then did I notice the sound of the wind and the waves. The song still reverberated from the surface of the water, but even its last murmurings vanished as I removed the tape and shoved it into my pocket. I staggered to the railing and looked down.

The mermaids were almost to Uncle Marlon. The old man was knee-deep in water, weaving against the tide, his hands outstretched to reach his wife. But the snow-white fish women turned around all of a sudden, dipped underwater and vanished in the foam. Their tails frothed the dark water as they moved rapidly away from shore.

I couldn’t understand Uncle Marlon’s words, but I could sense his overwhelming desperation. I saw him wade a few steps further in, then slowly lower both arms.

I could only feel disgust and pity. I still saw the face of the mermaid in front of myself. I stumbled to my duffel bag, picked it up and swung it over my shoulder. I looked around the enclosure saturated with light from the beacon, then I headed down the stairs.

When I stepped out the door, Uncle Marlon was tottering in. When he saw me with bag on shoulder, he froze and anger crossed his face. I forestalled him.

“This is not how it’s supposed to work,” I said. “I’m sorry… Really, I am. But it doesn’t work this way.”

“You know nothing!” he snapped at me. He was shaking from exhaustion. “How else could she have returned to me? I love her! You don’t understand anything! You have no clue about love!”

I looked him over, his worn and bone-tired shape, and my throat closed up.

“Maybe. But you don’t have one either. We should be ashamed of ourselves.”

I didn’t know if he’d heard my words over the roar of the wind and the sea, but I didn’t wait for his response. I hurried toward the path and the steps leading up the seawall, hastening my steps so that he wouldn’t be able to hold me back. The cold was starting to snake under the windbreaker, and sweat iced my back. By the time I reached the top of the cliffs, I couldn’t wait to get into my car and turn on the heating. Only when I was already gasping for air in the Ford did I realize that I didn’t even check if Uncle Marlon had gone back into the lighthouse. I didn’t get out. I drove to the closest fast food place and sat there until midnight. Then I drove home and listened to Ugly Kid Joe all throughout the long trip, washing the song of the sirens from my ears.

When I got home and opened the door, the first thing my gaze fell on was the pair of rabbit slippers. I threw down the duffel bag and just stared at the stupid slippers. Later, I called Kathy.

“Oh my God, do you know what time it is?” she protested, her voice mushy. My heart ached, and the thought flashed through me that I still had the tape, and if I played it to her over the phone, maybe she’d sense the summons and return to me. Maybe she’d stay with me.

“I know. I’m sorry.” I fell silent for a while, then I blurted it out, afraid she’d disconnect the call: “Kathy, you loved me, right?”

A moment of silence.

“Fuck,” she said in a forced whisper. “Is that why you called?”

“I just wanted to know.”

“Jesus Christ,” she groaned at me sleepily. “Are you sure you want to be having this conversation right now?”

I waited a bit.

“I don’t have the stomach for this,” she said, grumbling. “Does it matter whether I loved you or not if it’s all gone?” Her voice arced high, but when I didn’t respond, she softly sighed into the phone and broke off the call.

I put down the receiver. My hands were shaking. I sat on the sofa, peeled off my windbreaker and pulled the tape from its pocket. A few fragments of song were still buzzing in my ears, but it was also possible that this prickly longing feeling was tossing and turning around inside me for a whole other reason.

I saw Kathy step forward from the empty bedroom, her eyes open wide.

Tomorrow, I thought. Tomorrow I’d play her the song.

© Copyright Csilla Kleinheinez

Csilla Kleinheincz is a Hungarian–Vietnamese writer living in Budapest. She translates fantasy and science fiction and is currently an editor at GABO, a major Hungarian publisher. She is also founding editor of the online magazine SFmag (http://sfmag.hu). She has four fantasy novels and a short story collection, and her short stories appeared in English (Interfictions, Heiresses of Russ 2011, Apex Book of World SF 2, Sunspot Jungle anthologies) and various European languages.

Bogi Takács (e/em/eir/emself or they pronouns) is a Hungarian Jewish author, critic and scholar who’s an immigrant to the US. Bogi has won the Lambda and Hugo awards, and has been a finalist for other SFF awards.

Read the Rest of the October Issue

- The Ossuary at Ocean’s End by Marisca Pichette

- Elemental by Marlan Quade Cook

- portrait of a girl in water by Ashley Bao

- A Thousand Souls by Marie Brennan

- Seafloor Skull by Inkshark

- The Ghosts of Mermaids & The Answer Atop Mermaid’s Rest by Coral Alejandra Moore and Cathin Yang

- Awoken by Elyse Russell and Miranda Leyson

- The Abyssal Architect by Ori Jay

- One Last Shriek by Umiyuri Katsuyama

- Merfolks as a Passage from My Thoughts and Doings by Chinua Ezenwa-Ohaeto

- This Is Your Home by Stefan Slater

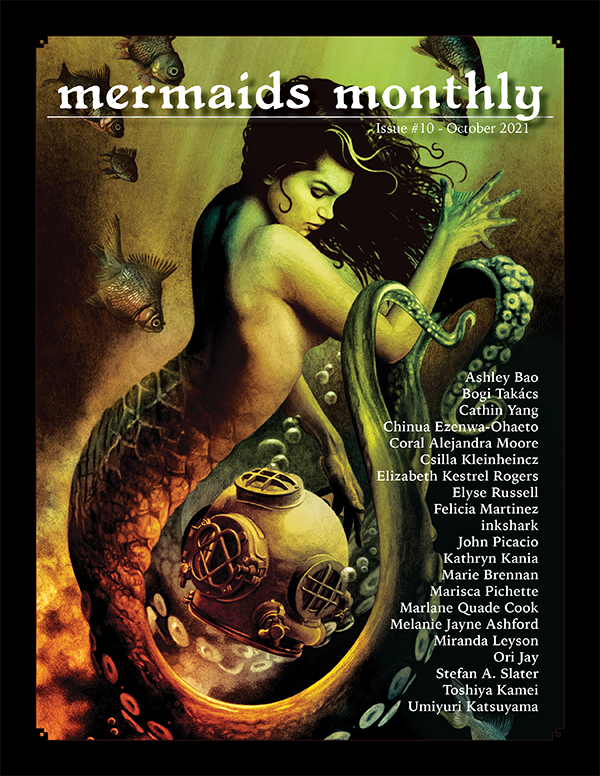

- Mermaidsong by Csilla Kleinheincz

- Fish Out of Water: How Mermaids Represent Disabled, Queer Folk Like Me by Melanie Jayne Ashford

- “a sea-like condition” by Felicia Martinez

- This Is You by Kathryn Kania

- Before You Go in Search of Spirits & The Truth They Hear in My Heart by Cathin Yang and Coral Alejandra Moore

- Dreams of Another Life by Elizabeth Kestrel Rogers

- Charting the Next Adventure by Meg Frank